The Work of Spring

Mr. Hadden Turner

The air outside is beginning to feel that little bit warmer and the sunlight that little bit brighter. The buds, which have lain dormant throughout the winter, begin to burst forth in verdant green, and out of last year’s decaying life, new life eagerly sprouts on the forest floor. As I walk along the bridleway that bisects the common land not far from my home, crocuses and snowdrops bedeck the frost-covered verges like fine jewels, and a passing brimstone butterfly — a dash of bright sulfur yellow — tells me only one thing: Springtime has sprung.

Spring is the season of return, the time when everything begins to stir again. With each passing day, the sun claims back its dominion over the night, temperatures rise, and winter recedes — all providing extra hours for labor. This cycle of light following darkness and its counterpart of work following rest form an unchangeable rhythm, a rhythm to which mankind has been subject from the dawn of time. We forget, perhaps, in our modern techno-dominated world — a world over which modern man believes he has absolute control — how dependent we are on the sun for life, energy, and activity and how bound and constrained we are to its cycles. And this dependency is by design.

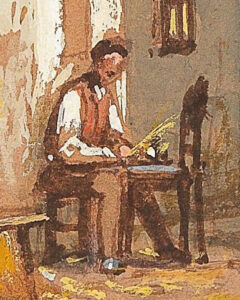

Although winter was a time of hardship, it was also a time of well-needed rest: hibernation for animals, dormancy for seeds and buds. And for us humans, it once was a time of “forced rest,” where diminished daylight hours (before the arrival of the electric lamp) constrained the work that could be done out in the field or even in the home. The ground, hard with frost or covered in snow, was not receptive to the plow or shovel, and candles inside the study could not keep burning forever. Planting would have to wait, and so too would those household projects that relied on daylight hours. So, instead of long hours at work, the hearth beckoned, heralding a time of warm nights in which stories could be told and retold around the fireplace, and tired bodies could recuperate from the arduous harvest season. Even in the present day, winter often takes on a slower working pace, especially for those who work close to the land. The limitations and constraints that cold weather and long nights bring cannot be fully overcome, even by machines.

The limitations and constraints that cold weather and long nights bring cannot be fully overcome, even by machines.

But now, with the change of the season and the arrival of spring, there comes an abrupt change in the yearly working rhythm. The time for prolonged rest is past; now is the time to return to work. Hard work. Earnest work. And all around me, life is bursting into action: Animals come out of their long hibernation; cuckoos, swallows, and willow warblers return from their winter migration; and crops shoot up from the warming earth. So too do weeds — lots of weeds. If the vegetable gardeners in the local allotments close to my home are slack with their weeding, weeds will dominate their plots and they will be subject to the shaking heads of many a passer-by. And it is not only the allotment holder and farmer who must “clean” their plots and fields:  Springtime is traditionally the time for cleaning the house — the famous spring clean— when windows can be opened again, the dust shaken out, and the soot cleaned from the fireplace.

Springtime is traditionally the time for cleaning the house — the famous spring clean— when windows can be opened again, the dust shaken out, and the soot cleaned from the fireplace.

In my own little suburban garden in the southern lowlands of England, I anticipate springtime with great delight and welcome its arrival with a flurry of activity. The plants that I have coddled during the late winter months can finally — once the last frosts have passed — be hardened off outside. Though they have appreciated the warmth of my home, there is no substitute for intense sunlight and its capacity to induce rapid and strong growth. Still, the outside does give rise to new challenges and dangers for my young seedlings. Pests must be removed or warned off — a relentless duty. A constant vigilance to detect late and unexpected frosts must be maintained, and a regular watering regime strictly observed.

At the other end of the country, on upland farms where lambing still occurs in the spring months, the shepherd must keep cautious watch over his flock. For his sheep, late frosts are not the issue. Instead, any of the myriad complications to which pregnant ewes are susceptible (and which may arise at any moment) are the cause of constant concern: large twins requiring a cesarean, a leg that has become twisted in the birth canal, or a stillbirth. These, and the multitude of other problems that birth can bring, demand the constant care and attention of the shepherd.

And so spring is a time of return: the return of light, the return of work, the return of life — but also of various perils. For risks always attend new life.

And so spring is a time of return: the return of light, the return of work, the return of life — but also of various perils. For risks always attend new life.

Spring is also the season of preparation. It is in spring that those working their gardens and farms prepare for the coming abundance: the gluts and harvests of late summer. The quality of the work done in this season of new life and growth will, to a great degree, determine the quality and quantity of the abundance of harvesttime. Fields that are well-sown, well-weeded, and well-manured from many long days in spring will — God willing — fill many barns come autumn. Conversely, slack hands in the spring lead to empty hands at the harvest.

Spring, therefore, is a time of not yet; the work done during these months is a down payment for future rewards. Spring necessitates the long view — a perspective that seems to have fallen out of favor with politicians and planners alike, to the detriment of our communities and farms. Instead, the exponential growth of the get-rich-quick mindset is chased after — the boom-and-bust pillaging that Mr. Berry so eloquently lambasts.  The good farmer, however, knows that the steady pace of creation, epitomized in the flow of the dependable seasons, is the rhythm he must dance to if the farm is to reap sustainable rich rewards.

The good farmer, however, knows that the steady pace of creation, epitomized in the flow of the dependable seasons, is the rhythm he must dance to if the farm is to reap sustainable rich rewards.

The farmer also knows, though, the painful truth that work does not always guarantee those rewards. Despite hard toil in many a past springtime, the ravages of the weather have in some years led to a time of “harvest-mourning.” A summer drought, spring floods, or late frosts. These and a host of other events can wreak havoc on the farmer and his crops. Though with less at risk, I too know this harsh truth all too well. Last year, the rain fell late in the summer and blight swept through my tomato plants like a forest fire, devouring almost everything in its path. I harvested what I could and was thankful for the sweet goodness I had already enjoyed from the earlier harvest. But to see so many good fruits, the labor of many months, succumb to rot and death was a bitter blow.

So, in the spring, I, along with every gardener and farmer up and down the country, sow and plant in faith: faith that the weather holds, the frosts pass, and the rain falls at the right time. I put my plants and my work in the hands of my Maker, who causes seed to grow. And I trust.

But this does not mean my work and duties stop when trust begins. Far from it. All through the year, new challenges, tasks, and obligations arise as crops and fruits develop, but (at least when I am at my best) my disposition of trust and dependence remains. I can work hard to provide what my plants need, but only the God who orders the universe can make them grow. Springtime, then, is also a time of trust — the trust that he will richly provide from the work of his stewards.

It is for our good that there are distinct seasons, for our Maker knows our needs and our tendency toward waywardness. He knows our propensity to live out of rhythm with our limitations and with creation, as we too easily obey the cruel masters of overwork or sloth. He knows our deep temptation to expect too little and too much of ourselves. He knows us all too well. Thus, he has provided us with an unchangeable reminder of the need for both work and rest, both risk and renewal, both preparation and trust. “While the earth remains, seedtime and harvest, cold and heat, summer and winter, day and night, shall not cease.” And so it is that in spring, all of us must rise from our rest and return to the faithful work God has called us to, whether that be sowing and weeding in our fields, caring for and nurturing our children, studying and revising for our exams, or making and selling our crafts and wares. There is plenty of work to be done — summer is coming.